Being a conservation organisation, we’re always trying to do our bit for nature by providing numerous nest boxes for our native birds to use.

Our Education Officer, Susan, has been a nest recorder and bird ringer for years, so she has taken responsibility of monitoring any nests on site and submitting the records to the British Trust for Ornithology. Here, she talks of the mixed results this year.

The season seemed quite late this year, with the first eggs laid about a week later than last year. Of the boxes we have up, two are in relatively high disturbance areas, yet these are consistently the ones used! Maybe a clever tactic as more humans passing by might deter predators?

The one located in our compound area was claimed by Jade, while the one on Lincoln’s aviary was claimed by Mat. Over the next week or so, Jade won on timings as her eggs were laid first, and therefore hatched first, about a week before Mat’s!

Hatching day for the compound nest - lots of hungry mouths to feed!

Blue Tits will lay one egg a day, up to 10 or 12 eggs in total. The female will start incubating when the last, or sometimes second last egg has been laid, so that all of the eggs hatch synchronously within 24 hours of each other. This is a great strategy as Blue Tits play the numbers game, so that if all their chicks survive to fledging, they flood the local area and hopefully some will avoid being predated.

Female Blue Tit keeping her eggs warm on Lincoln’s aviary

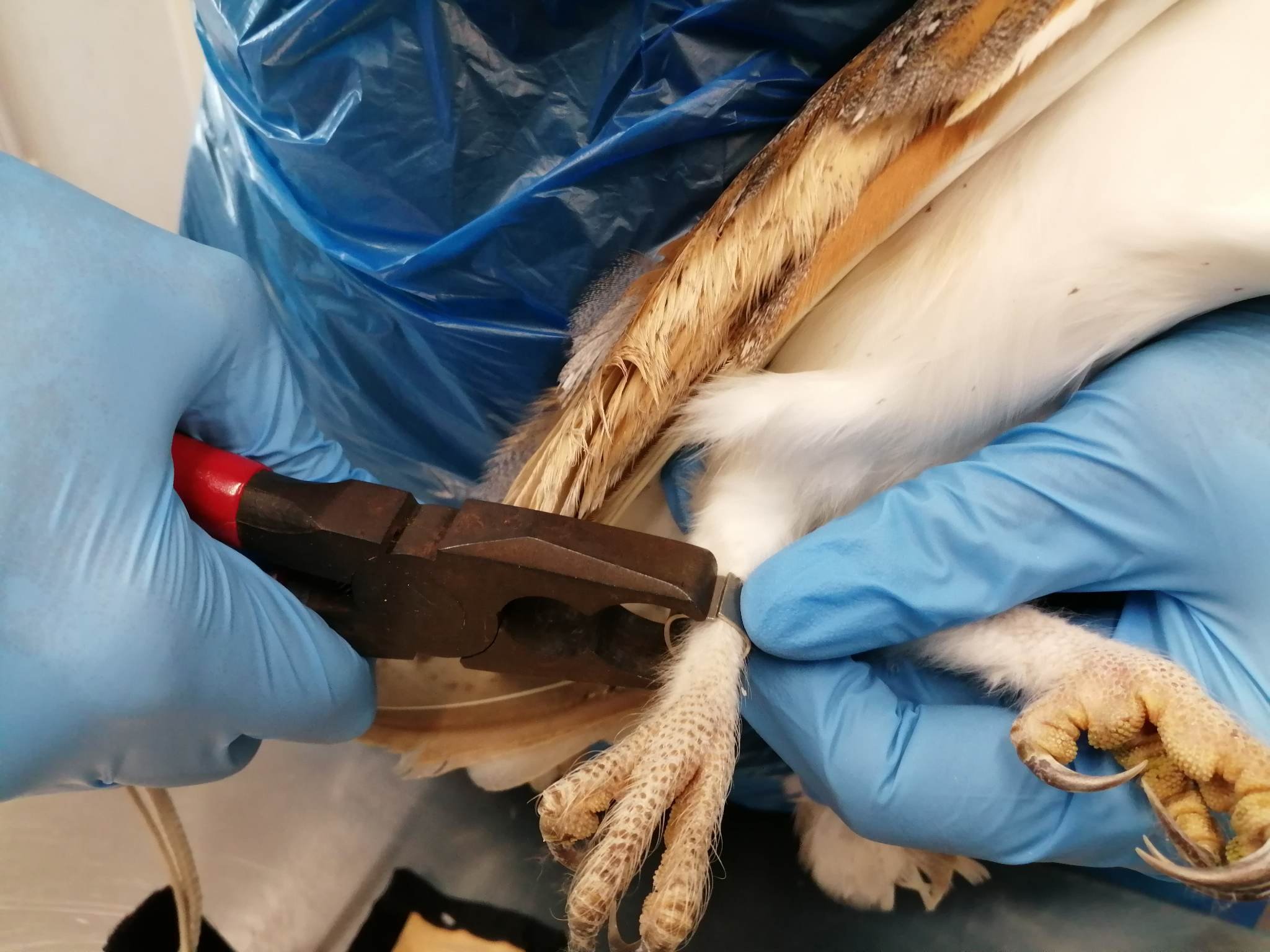

A week after hatching, most of Jade’s chicks were ringed, however, three were too small to have a ring so returned to the nest.

A young Blue Tit about to receive a ring

A few days later, Jade informed me of a surprise nest in the Woodland Walk. This box was well hidden behind one of our log stacks, and I had completely missed it on my initial check of the boxes. What makes this even more remarkable is that we were working on the shelter at the back of the Flying Ground (within 1m of this box) well into the usual breeding season, so had written off the boxes in this area due to the high disturbance! This family must have moved in the day the work stopped, as when I opened the box I found it full of Blue Tits ready to fledge!

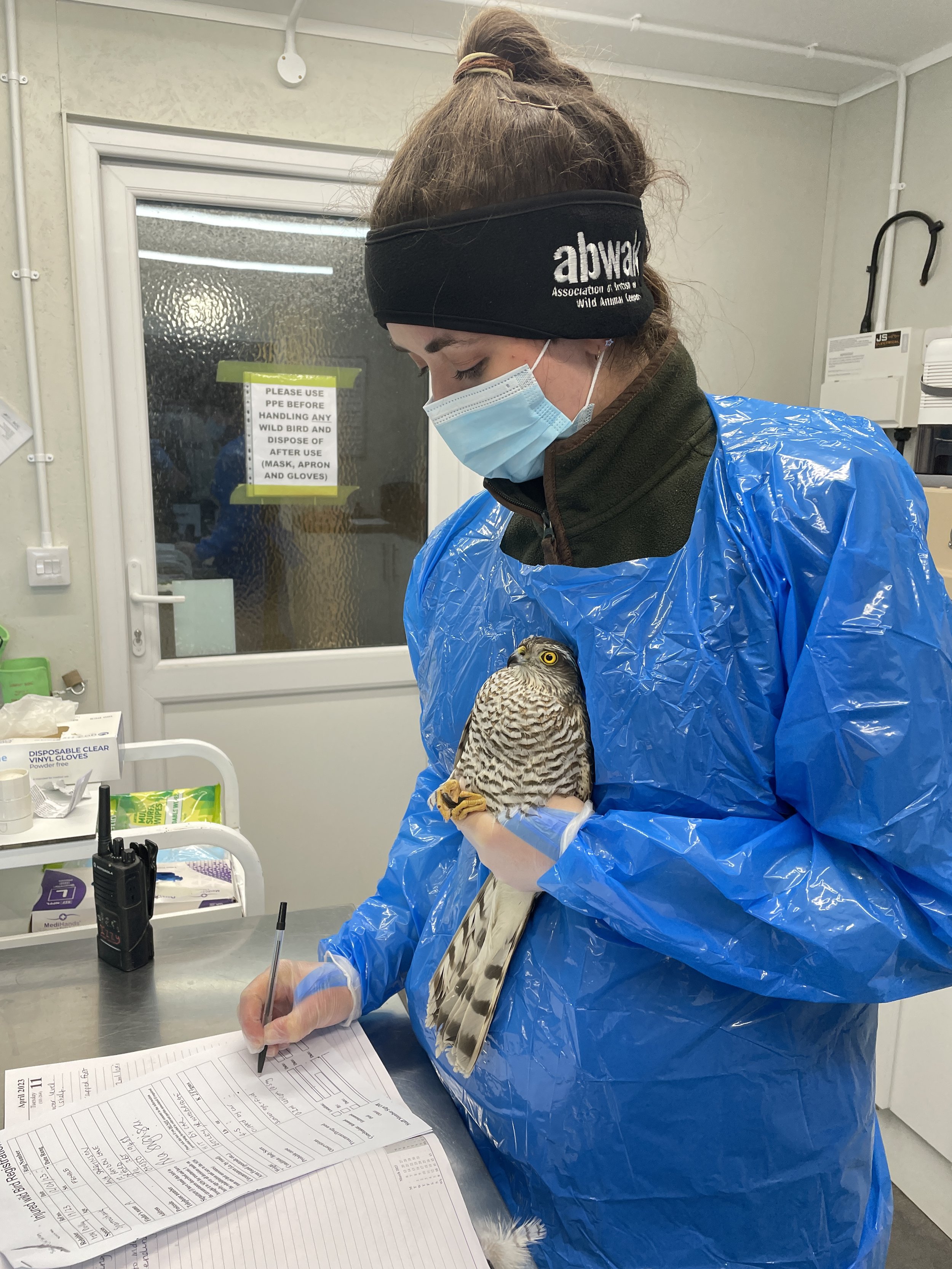

This little Blue Tit doesn’t look too happy about becoming a science bird!

We quickly gathered them all into a waiting bag, and proceeded to ring each chick before returning to the box. While this was going on, mum and dad were sat in the trees above us, chirping their concern as we gently handled their offspring. All chicks were returned to their nest, but by the end of the day at least four chicks were seen in the trees, now with a tiny ID ring on their legs.

I returned to check Jade’s original nest in the compound and was disappointed to pull out two very recently deceased chicks. Both these chicks were what can only be described as skin and bone, and we suspect that they only had one parent. There were three remaining chicks in the nest, and one of these was unringed, so it was quickly given a ring and returned to the box as mum came back with a beak full of insects.

Mat’s nest had by now hatched, and were probably big enough to ring. However, given the delayed growth of the compound nest, I opted to give them an extra couple of days just to make sure. The difficulty in judging whether they’re all big enough to ring is that the smallest chicks are usually at the bottom of the nest, and removing all the chicks to check causes unnecessary disturbance if you must return a few days later to ring the smaller chicks.

Are they ringable?

When we checked on them a few days later, they were all a good size and well feathered. From this nest, all ten eggs had hatched and survived, which was fantastic to see! I invited staff and volunteers to come and watch, and each chick not only received a unique ID ring, but also a “pet name” based on their looks or behaviour during the ringing process!

Einstein, due to his scruffy fluff

Puddle, as this little one seemed to melt into my hand (this is a defence behaviour)

The purposes of ringing chicks such as Blue Tits in the nest is to determine fledgling survival. Most of these birds won’t survive to breed themselves next year, but by ringing them we can monitor how many do. To highlight this, Susan caught two of the three mums while they were incubating their eggs, and was excited to find one already had a ring on. When she looked back through last year’s ringing data, this was actually ringed as a chick last year, showing it survived to breed and is showing site fidelity by nesting in the same box it hatched from in!